African Americans staked their claim in golf more than 100 years ago but getting on the green was not without its struggles.

By Carolyn Grant

Blacks, and other people of color who had the opportunity to learn and play the game faced rejection because of their skin color. With the passion they had for the game, they fought for the right to enter tournaments, to play and to simply be respected as golfers just like their Caucasian counterparts.

Historical research links African Americans to the game of golf as far back as the later 1790s during the days of slavery. Primarily slaves were used to scout holes for play for their owners, to clean and polish golf clubs and to perform other duties related to the game.

But the real entry to golf for blacks didn’t occur until 100 years later in 1890. From that point on, black made remarkable strides that proved good for the game but didn’t necessarily earn them the recognition they deserved. Many of their accomplishments were the first among all Americans but are recognized last – if at all – in the world of golf.

There were several African Americans – John Mathew Shippen, Jr., Dr. George Grant, Walter Speedy, Joseph Bartholomew and others – became pioneers in their own right and set the course for other Black golfers to follow and make the game accessible for all who wanted to play. The most prominent probably is Shippen, who is noted as the first golf professional to be born in the United States and the first African American to play in the U.S. Open. Shippen, who came from a well-to-do family, quit school to take up golf full-time. His foray into golf began in the early 1890s on the Shinnecock Indian Reservation (in Southhampton on New York’s Long Island), where his father, a Presbyterian pastor, had been sent to minister.

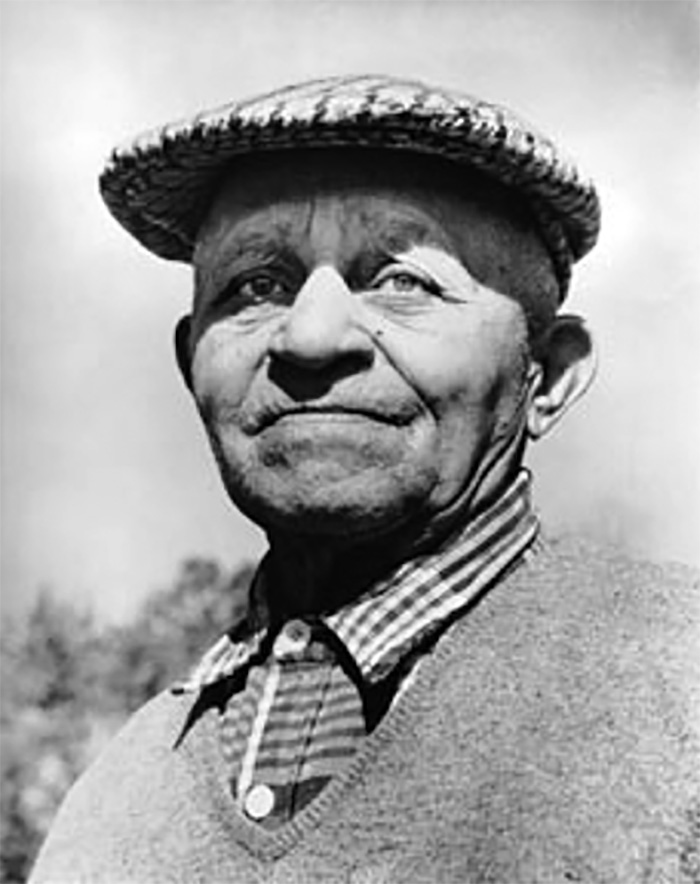

Shippen, along with Native American Oscar Bunn, was one of the laborers who helped to construct the course at Shinnecock. He was also trained as a caddie and became quite skilled at the game. His talents earned him the position of assistant to the professional. He gave lessons, kept score, and performed other duties. In 1896, when the United States Golf Association brought this second U.S. Open Championship to Shinnecock, Shippen, teamed with Bunn, had an opportunity to play.

However, on the day before the competition, other golfers threatened to drop out of the tournament if Shippen and Bunn played. But Theodore Havemeyer, the president at the time, was adamant that they play. The competition opened with Shippen and Bunn in the field. Shippen played incredibly well the first day. On the next day, he lost ground when his ball landed in a sandy road and he struggled through the rest of tournament, finishing seventh. Shippen spent the next years of his golf career working as a private instructor for wealthy men and various African American owned golf clubs.

There were golfers that made pioneering moves in golf. Dewey Brown, born in 1898, began caddying at the age of eight, eventually becoming a golf instructor and maker of golf clubs. In 1928, he became the first African American member of the Professional Golfer’s Association.

Dr. George Grant, a dentist, invented the golf tee and received a patent for it in 1899. Joseph Bartholomew, born in 1881, became one of the leading golf course architects in the New Orleans area.

Although Blacks made some waves in the golf world and took on the hard task of caddying for many years, they still sought to make a presence in this sport but continued to battle racism and indifference along the way.

“Golf’s popularity among the non-caddying ranks of African Americans began to emerge in the years shortly before the entry of the of the Unite States into World War I. The spread of golf courses in cities of the Northeast provided black novices with a place to play, and gradually they began to be seen on municipal links,” Calvin H. Sinnette, writes in his book, “Forbidden Fairways, African Americans and the Game of Golf.”

It was in this era that Black golfers began to organize their own clubs so they could obtain some significance for their talents and abilities. To mention a few, there was the Pioneer Golf Club, organized by Walter Speedy and others in Chicago around 1910. In 1915, another club – the Alpha Golf Club – sponsored the first Negro National Golf Tournament. The St. Nicolas Golf Club was organized in 1926 in New York City and the Capital City Golf Club came into existence in 1928 in Washington, D.C.

Along with those clubs came the formation of the United States Colored Golf Association in 1925, and it later became the United Golfers Association (UGA). These organizations gave blacks the opportunity to dominate their own ranks and produce their own golf champions, some that eventually broke through PGA barriers. The organizers hosted their own events for Black golfers.

“By the 1920s, Blacks and other non-whites were not welcomed at United States Golf Association events, and the PGA shunned and discouraged Blacks from participating,” according to Pete McDaniel’s “Uneven Lies, The Heroic Story of African Americans in Golf.”

The UGA, by the 1930s, took Black golfers to new heights, dividing itself into districts of Black clubs around the country and producing golf stars as John Dendy and Robert “Pat” Ball. The UGA became a driving force in Black lifestyle.

Pete McDaniel writes in his book that “by the 1940s, the UGA had become not only the training ground for top African American golfing talent such as Zeke Hartsfield, Bill Spiller, Teddy Rhodes, Charlie Sifford and Lee Elder; it was a sanctuary for a unique subculture. The Black golf tour touched almost every aspect of African American life. From beauty salons to restaurants, the local business community benefit from the influx of revenue during tournaments.”

The UGA provided a social outlet for Blacks as well with galas and balls featured top entertainers such as Cab Calloway and Duke Ellington and sports figures such as boxer Sugar Ray Robinson and baseball player Jackie Robinson.

The UGA was the sponsor of the annual National Negro Open that was played on public golf courses in different cities. During those days, in an era plagued with civil rights and racial discord, public golf courses where the only places Blacks were allowed to play and host their tournament. Even then, their use of the course was only for a limited time.

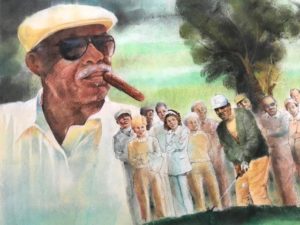

Charlie Sifford, the first Black golfer on the PGA, made a name for himself through the National Negro Open, winning the tournament several times. In his memoir, “Just Let Me Play” – “The Story of Charlie Sifford, the First Black PÀGA Golfer,” Sifford describes his break in the summer of 1946 when he was invited to play in the National Negro Open in Pittsburg. Although he didn’t win that year, Sifford said the tournament exposed him to longtime friendships and fierce competition.

“What I remember most about the tournament wasn’t the play itself, but the friendships I made. Suddenly, I was running in a circle

with Joe Louis and Sugar Ray Robinson, alongside black golf legends like Teddy Rhodes and Bill Spiller. In the space of a week, I was transformed from a guy who played a pretty good game back in Philadelphia to a professional who could hold his own against the best black pros of my day. I was suddenly surrounded by a group of black guys who loved the game as much as I did and loved to talk about the shots and the tournament and the competition. It was exactly what I had always wanted,” Sifford wrote in “Just Let Me Play.”

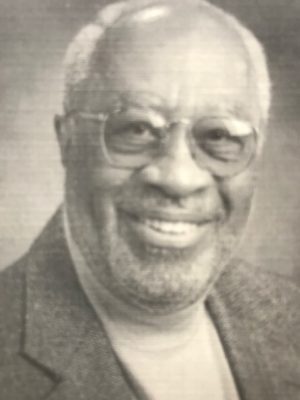

Sifford, never afraid to speak his mind, learned early® on that he had to fight for opportunities to play in white tournaments, particularly those sponsored by the PGA. An important break happened for him in 1957 when he played in and won the Long Beach Open in southern California, a PGA sanctioned tournament – the first black to win a PGA event. Yet, the win didn’t earn him admission into the PGA, which still refused to admit blacks. Threats from California’s attorney general’s office in 1960 forced the PGA to drop its white-only clause and give Sifford a player’s card, according to Sifford’s memoir. Sifford’s battles and determination to play in and be a part of PGA events continued through the 1960s. In August of 1967, he claimed a PGA Tour victory when he won the Greater Hartford Open and received the $20,000 prize check.

Other golfers also encountered the reactions and rejections that Sifford faced as well. Their handling of the situations and persistence changed the color of golf so others could benefit.

Robert Lee Elder, more popularly known as Lee Elder, was the first African American golfer invited to play in The Masters in Augusta, Georgia. He joined the PGA Tour in 1967. In 1974, he won the 1974 Monsanto Open – becoming the first African American to win a PGA victory since 1969. In 1984, he joined the Senior PGA Tour.

Others who made a name for themselves on the PGA Tour include Calvin Peete, Jim Thorpe, Charles Owens, Jim Dent, Walter Morgan, Bobby Stroble and Pete Brown.

African American women also helped paved the way for golfers and helped to popularize the game among other blacks. Among them were Ann Gregory who was the first African American to enter the U.S. Women’s Amateur in 1956 and Maggie Hathaway who, in 1958, started a campaign to gain membership in the all-white Western Avenue Women’s County Golf Club in Los Angeles. Hathaway is remembered well for her golf columns and features she wrote as a journalist for the Los Angeles Sentinel, from 1963 to 1996.

Like their male counterparts, women also suffered racial barriers in the game. But, in addition, they fought male dominance and chauvinism. Sinnette describes his book how a series of disputes at the third Joe Louis Open in 1946 led to them being excluded from the tournament in following years. African American women were also disturbed about not having leadership roles with the UGA.

Despite the barriers, African American women, such as Althea Gibson, still made a name for themselves in golf. Gibson first claimed some victories in tennis. In 1950, she became the first African American woman to compete in the National tournament of the United States Lawn Tennis Association at Forest Hills; and as a singles player, she won her first Grand Slam event at the 1956 French Open, Sinnette writes. Gibson began focusing on golf in the 1960s, turning professional in 1963. A year later, she became the first African American golfer on the LPGA tour. Other African American women who qualified and play on the LPGA tour are Renee Powell and La Ree Pearl Sugg.

Powell joined the LPGA in 1967 and played on the tour for 12 years. Sugg, according to Sinnette, made her debut at the 1995 Cup Noodles Hawaiian Ladies Open; this event marked the first time in 17 years that a Black golfer appeared on the LPGA tour.

Today, African Americans are still breaking barriers in the world of golf, especially with the successes of Tiger Woods, who captured 15 Major titles, 82 PGA Titles, and over 100 titles worldwide.

In addition, African Americans are building careers on the administrative and operations side of golf, holding high executive positions, including the recent appointment of Fred Perpall of Dallas, Texas, as the 67th president of the United States Golf Association.

Coming through the decades has been challenging, but Sifford, Elders, and others never gave up on the game and never stopped pushing for opportunities for themselves and others. Woods and others behind him will set the new course for the next 100 years.

The story of African American golfers and their struggles and successes – from the earliest history of golf through the present-day have been vividly and thoroughly captured in Pete McDaniel’s “Uneven Lies,” Calvin Sinnette’s “Forbidden Fairways,” and Charlie Sifford’s

“Just Let Me Play,” and “Invisible Golfers: African Americans’ PGA Tour-Quest by Jeffrey JC Callaway.

Note: This article has been edited and updated by the MGM staff.