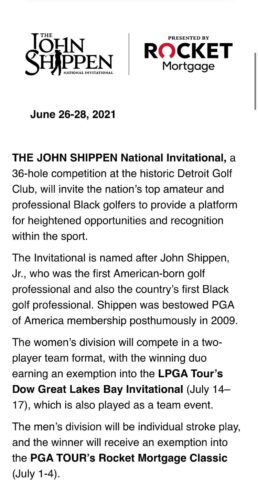

Editor’s note: Lenwood Robinson, author, historian penned a novel in 1996 called the Black Golfer, a Chicago Perspective. His work and writings on Black Golf in America is as relevant today as it was twenty-five years ago. Minority Golf Magazine chose to print excerpts in it’s February 1997 issue and the story remains important today as the PGA and the Chicago Golf Club (site of the 2021 Rocket Mortgage PGA tournament) prepare to host a national co-ed tournament featuring a field of top African American male and female golfers from around the country.

The Women’s Division will feature a 36-hole competition with a two-player team format. The winning duo will earn an exemption into the LPGA’s Dow Great Lakes Bay Invitational (July 14–17), which is also played as a team event.

The Men’s Division will compete in a 36-hole individual stroke play event, with the winner receiving an exemption into the PGA TOUR’s Rocket Mortgage Classic (July 1-4).

The American Black Golfer – A Chicago Perspective. Ch3

By Lenwood Robinson

In reference to the history of golf in America, Don Weiss wrote in USGA’s Golf Journal, “The Guinness Book of World Records deals in superlatives: longest, biggest, highest, fastest and most; however it doesn’t have too many ‘oldests’. Oldest are not usually current, but oldest means first and the first of anything is important and intriguing.”

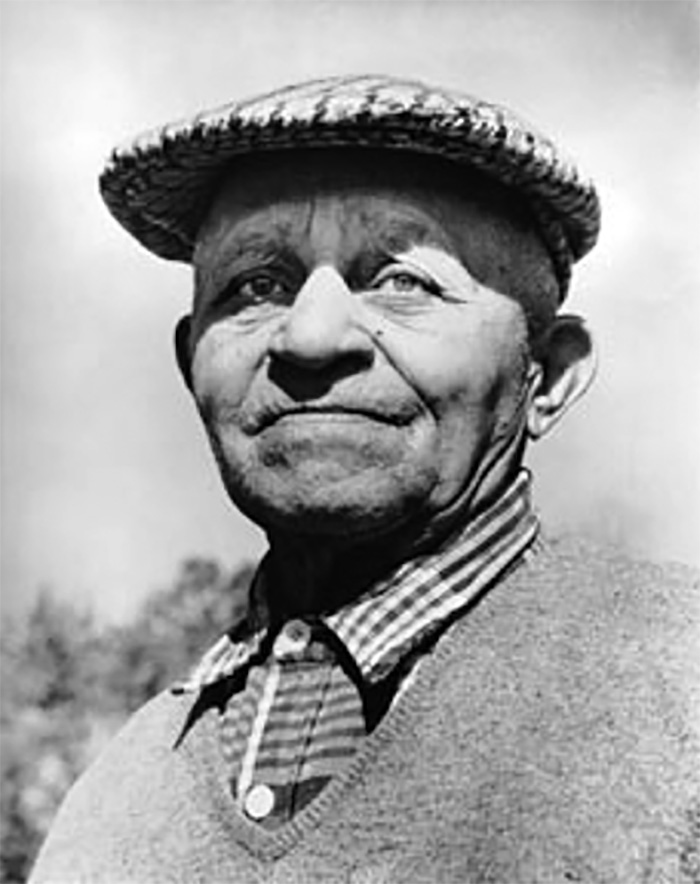

There have been many firsts in almost every aspect of American life and existence. Because golf was considered for the rich and white, many people knew but forgot that a Negro, John Shippen, was the first American-born golf professional, and that this same man, for a dozen years at least, was one of the finest players in his era.

In 1896, at the tender age of 18, John Shippen, an unexpected skilled performer and great athlete, astounded the world by making a valiant run for top honors in the second U.S. Open Championship, played at Shinnecock Hills Golf Club. He was in the lead with five holes to play when disaster overtook him on the 13th hole, where he took 11 strokes—seven strokes over par and seven strokes behind James Foulis, the eventual winner.

Shippen tied for fifth with a 78-81 total of 159 in the 36-hole tournament, following G. Douglas and A.W. Smith who tied for third at 158, Horas Rawlings at 155, and James Foulis, who shot a snappy (for those days) 74 in the round for a 152.

Although by World War I his career had faded, history records Shippen as the first American-born golf professional. For a dozen years, he was one of the finest tournament players in the country and, for 50 years, was a successful teaching professional at golf courses in New York, Maryland, and New Jersey.

Shippen can be compared to Jackie Robinson, Jesse Owens and Joe Louis because his preeminence in a sport so avidly followed by Americans has greater implications outside the world of sports. His life was a testimony to the potential of Black people in any arena in which they choose to participate and serves as a model of excellence for today’s young Black golf aspirants.

Shippen can be compared to Jackie Robinson, Jesse Owens and Joe Louis because his preeminence in a sport so avidly followed by Americans has greater implications outside the world of sports. His life was a testimony to the potential of Black people in any arena in which they choose to participate and serves as a model of excellence for today’s young Black golf aspirants.

Did other Black professional golfers such as Ted Rhodes, Bill Spiller, Charlie Sifford or Calvin Peete know about Shippen? Maybe. Did Tiger Woods commemorate Shippen during Black History Month?

John Shippen, the son of a Black man and a full-blooded Shinnecock Indian mother, was born in Anacosta, Washington in 1878. His father, a Presbyterian minister-school teacher, couldn’t earn enough money to support a large family, so when he was offered a post as a teacher and minister, near the Indian reservation at Shinnecock Hills, Long Island, he decided to raise his brood there.

As fate would soon issue rewards, the nearby 12-hole golf course in Southampton provided a steady source of income for young boys with strong backs and willing legs. Enter Willie Dunne, a Scotsman who came to this country in 1891, described as the nation’s first golf professional, supervised the construction of Shinnecock Hills. He relied heavily on the local Shinnecock Indian reservations for laborers and eventually trained young Indian boys as caddies. One of his caddies was John Shippen. In addition to working on the maintenance of the course and caddying, Shippen developed a very credible golf game. Eventually, he served as Dunne’s assistant, giving lessons, repairing clubs, acting as a starter and scorekeeper for tournaments.

Ken Davis, who caddied for Shippen in 1903 and 1904, remembers Shippen’s playing ability. “He was an excellent driver. He could outdrive anyone playing at the time. And remember, those were the days of the solid golf ball and wooden-shafted clubs, he said. “Many a player would bet him a dollar they could outdrive him. In all those years, I never saw but one man who could outdrive him.”

Prior to that fateful day in the Open, Shippen made a decent living from playing exhibitions, caddying, and in the winter, he performed groundskeeping and clubhouse chores. Golf then, of course, was not the cornucopia of riches as it is today. For instance, for his fifth-place finish in that 1896 U.S. Open, he received a purse of $10. Caddies picked up a quarter or half-dollar for an 18-hole round. “But John would get up to $5 a round for teaching,” recalls Gordon Williams, an old friend. “He was very popular with the members, and he’d play a round with all of them. There wasn’t so much prejudice then on the golf courses. Especially with the rich. You were more a part of them.”

Charlie Thom, a Scotsman who was the pro at Shinnecock for 55 years, remembers Shippen as “a very nice fellow and quite a golfer. “In two matches he beat me in 23 holes and then I beat him in a rematch that had all the members betting.”

Shippen himself recalled beating the great Willie Park at Shinnecock when he was a 17-year-old caddie. “Park was going to play Willie Dunn, the club pro, the next day and wanted me to show him the course. When I beat him, he gave me $5 not to tell Dunn. The next day, I trimmed Dunn 13 and 12, the worst beating I ever saw anyone take.”

Encouraged and financed by wealthy white backers, many of them his students at various Long Island country clubs, Shippen played in four more U.S. Opens: 1899, 1900, 1902 and 1910. He finished tied for 5th in 1902 at Garden City Golf Course, New York behind Laurie Aucterlonie, and tied with Willie Anderson, the defending champion who would win the next three Opens. At Baltimore in 1899, he finished near the bottom as Alex Smith ran away from the field by 11 strokes. At the Chicago Golf Club in 1900 Shippen placed in the middle of the field. The great Harry Vardon won that one. Shippen was still competing as a touring pro as late as 1913 when Francis Ouimet, in the historic Open at Brookline, defeated Vardon and Ted Ray in a playoff.

Shippen’s competitive golf career faded into obscurity. The real reason why has not been documented. The world soon forgot that a Negro was the first American-born golf professional and this same Negro, for a dozen years at least, was one of the finest players his era produced. Comparing his era of golf with the Modern Age of Golf, Shippen recalled, “The great players of my day would have been a match for the great players of today. Willie Anderson and Alex Smith would hold their own with Jack Nicklaus, Arnold Palmer and Gary Player. So could Walter J. Travis, Harry Vardon and Jerry Travers. The players of today have all the best of it. They have precision clubs, a much livelier and more accurate golf ball, and the courses are in much better shape. But the good ones in my day shot in the low 70s. And they never carried more than nine clubs.

Moving to his personal saga, Shippen married twice. Both of his wives were of the Shinnecock Indian tribe. His first wife died young; his second wife bore him two sons and four daughters. “We had a nice frame house, very large, and we were a very content family,” recollects Mrs. Clara Johnson, his youngest daughter, who lives in Washington D.C. She is retired from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing and later worked as a supervisor in the book shop of the National Collection of Fine Arts in the Smithsonian. “I remember my father leaving the house early in the morning with Charles Martinez—he was an Apache—to work at the golf course. They’d have to walk four or five miles, but they knew all the shortcuts through the woods.” she said. “I remember they used to call my father, “The Iron Man” because he was so wiry and healthy. He never even caught a cold.”

Mrs. Johnson also remembers how she and her brothers and sisters had to walk three or four miles to a one-room schoolhouse every day, a situation that displeased Mrs. Shippen. “My mother was a well-educated woman who spent two years at the Normal School in New Platz, New York, and had to teach on the reservation. She wasn’t satisfied with the education we were getting in our little school, so she talked my father into moving down to Washington D.C.,” Johnson said. Reluctantly, Shippen agreed to leave his cherished Long Island golf courses. “He worked in a government job, an inside job for 4 or 5 years, but he really disliked it. He had to be outdoors. He had to be around a golf course.”

Sometime later, Shippen became affiliated with a course for Negroes near Laurel, Maryland. He laid out the course, grew the greens, developed the fairways, worked in the clubhouse, and gave lessons. But after several years, the project went under because it was too far out from the city. There weren’t so many cars then, and Negroes had few of them.

By 1925, Shippen had found his niche—the Shady Rest Country Club in Scots Plain, New Jersey, where he would spend the next 35 years as a teaching pro. Formerly the Westfield Country Club, Shady Rest was established in 1921 and reunited a significant focus of Black culture for the next 45 years. Shady Rest was the first Black country club in America, boasting a full schedule of golf and tennis tournaments as well as social events. The first National Colored Golf Championship (or International Colored Championship) took place at Shady Rest over the fourth of July weekend in 1925. Shippen competed and finished 32 strokes behind Harry Jackson of Washington D.C., winner of the 72-hole event with a score of 299; the first prize was $25.

The decades drifted by the Thirties, Forties, and Fifties. Shippen’s children grew up, all of them going to college and on to their careers. John Jr., the eldest, who is now deceased, worked for the government in D C. Mrs. Mable Hatcher worked for the Washington D.C. school system, and Beulah Shippen worked for Civil Service. Both are retired and presumably live in D.C..

“My father drifted apart from us as we grew older,” Mrs. Johnson says. “And there was a long stretch of years when we didn’t even know where he was. Then one day, my husband and I were playing golf in a Scotch foursome at a New Jersey course and a man asked me if I was John Shippen’s daughter. He told me my father was at Shady Rest. We went up the next Sunday and had a wonderful reunion. He was around 75, but he played a round of golf with us. He skipped some of the longer holes, but he could still drive well. You can ask my husband because my father outdrove him on the first hole.”

John Shippen had one last moment of glorious satisfaction, years ago, when Charlie Sifford played in the U.S. Open. It was generally assumed that Sifford was the first Negro to compete in the tournament, but a golf magazine turned up with Shippen in an interview, and observed, “If he exalted the players of his own day, who would blame him.”

In an effort to inform the golfing public of the significance of John Shippen and Shady Rest, The Shady Rest Country Club/John Shippen African-American Historical Commemorative Committee was formed in Scotch Plains to honor the accomplishments of Shippen and to designate Shady Rest an historical site. In 1991, Lee Elder conducted a junior golf clinic at Scotch Hills to call attention to the legacy of Shippen, and a celebrity golf tournament was played in October 1991 at Scotch Hills to raise funds honoring Shippen with a scholarship and proper monument.

Shippen was still playing golf when he was 80 years old. He died July 15, 1968 — at the age of 90. He was proof that the Black American Golfer had been involved, historically, in the growth and popularity of golf. He attests to the fact that America has done nothing since 1619 in which Blacks were not, in some way, intimately involved. It is essential that the little-known saga of John Shippen be revealed. From an Afro-American historical perspective, there is a need for Black golfers, especially juniors, to have role models, their very own Nicklaus or Palmer to look to with pride.